With more and more women working, plain sarees suitable for office have become popular and certainly such sarees which rely on colour have their charm. But what distinguishes most handloom weaves are their motifs. Certainly it is true of Chanderi. The motifs as with many weaving clusters come from nature and history all modified by the hands of the men and women who weave sarees.

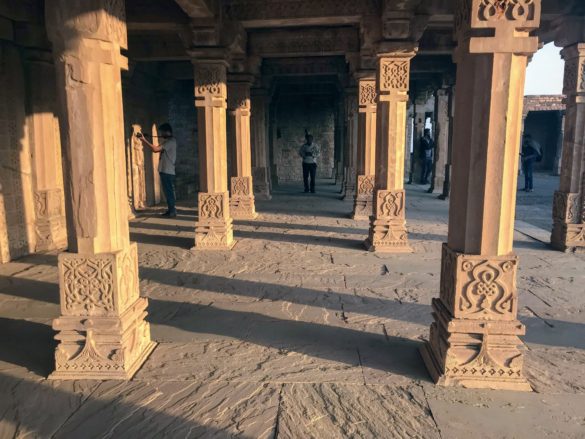

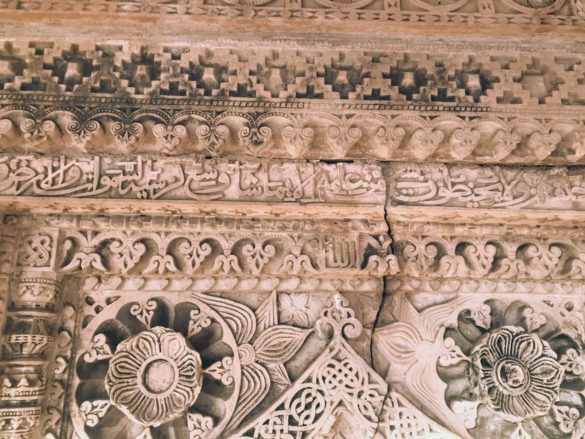

Walk around town and you can see the inspiration for the motifs everywhere. The pillars and walls of the Khila Kothi have carvings as does the Chanderi museum. All of this provide fodder for the weaver.

These days, however, anything goes. Says Zamarrud, the wife of master weaver Aminuddin Ansari, “We get inspiration for motifs everywhere. I may look at a movie, or a butterfly, or a painting and see something that could be a motif. So we quickly take a photo of it and Whatsapp it to each other. From the photo comes the freehand drawing and then the punched motifs. And finally to the loom.”

Chanderi, unlike say, Kanchipuram is very advanced with respect to inventing motifs. There are fans, umbrellas, ear-rings, fruits like pineapple and pomegranate, and of course, flowers and vines from nature. The one on the left is a classic “jhumka” earring design woven into a saree.

The most common Chanderi motif is the ashrafi or the coin motif. The ashrafi butti, as it is called has many variations. Other motifs have to do with marital wishes. The “Sada Suhagan” motif is given to young brides so that they can stay as married women their entire lives, and die before their husbands to be frank. Modern day feminists including me might view these motifs as archaic and sexist. But there you have it. The long arm of Indian tradition.

Other wedding motifs include “Mehendi lagi haati,” which shows two hands with henna on them, also a wedding ritual. Similarly, the palanquin motif woven on the border is the epitome of the old Indian bride being carried to her husband’s home before cars were invented. A beautiful idea but in this day of LGBTQ and live-in relationships, so out of date.

“The way one sees is also dependent upon one’s emotional state of mind. This is why a motif can be looked at in so many ways, and this is what makes art so interesting.”

Edvard Munch

A better idea for sarees would be lines such as “#MeToo” or “And still, she persisted,” instead of “Sada Suhagan Raho.” But that is the job of a designer. Consider the below art by artist Courtney Privett. Any of the lines could apply to contemporary sarees.