My name is Shrikrishna Somani and I am 88 years old, he began.

Somani-ji runs Gopilal & Sons, a reputed Chanderi weaving company that his father started in 1955. Now his grandsons manage it. S.K. Somani-ji belongs to a Marwari family who have now lived in Chanderi for four generations. He is a repository of stories and myths.

King Shishupal, Krishna’s cousin, and the Chanderi weave

Take a simple one. Some tales state that Chanderi weaves existed since the time of King Shishupal, who was Krishna’s cousin. Somani-ji waves that away. These sarees are far more recent, he says. Post-Independence in fact. Before that, it was all safas (turbans).

The Kolikanda Root

Another story is about the kolikanda root. Rta Kapur Chishti’s book, “Sarees: tradition and beyond,” says that traders used to forage surrounding forests for this root to size the traditional yarn. “It was light on the yarn, giving it a lustre and roundness even as it strengthened it.”

Somani-ji says that it may well have been true, but that was before the Chanderi became the Chanderi as we know it. Today the production output demands mechanization: cotton yarn from Coimbatore in the South, silk from China, and zari from Surat.

Like most people, he walks us through the history of how the translucent Chanderi cottons were used for royal turbans for the ruling families from Kolhapur, Indor, Pune, Gwalior, and all over North India. “Royalty bought it for daily wear and for functions. In fact, the sarees were so long that two women would walk behind the queens holding the pallu like a train.”

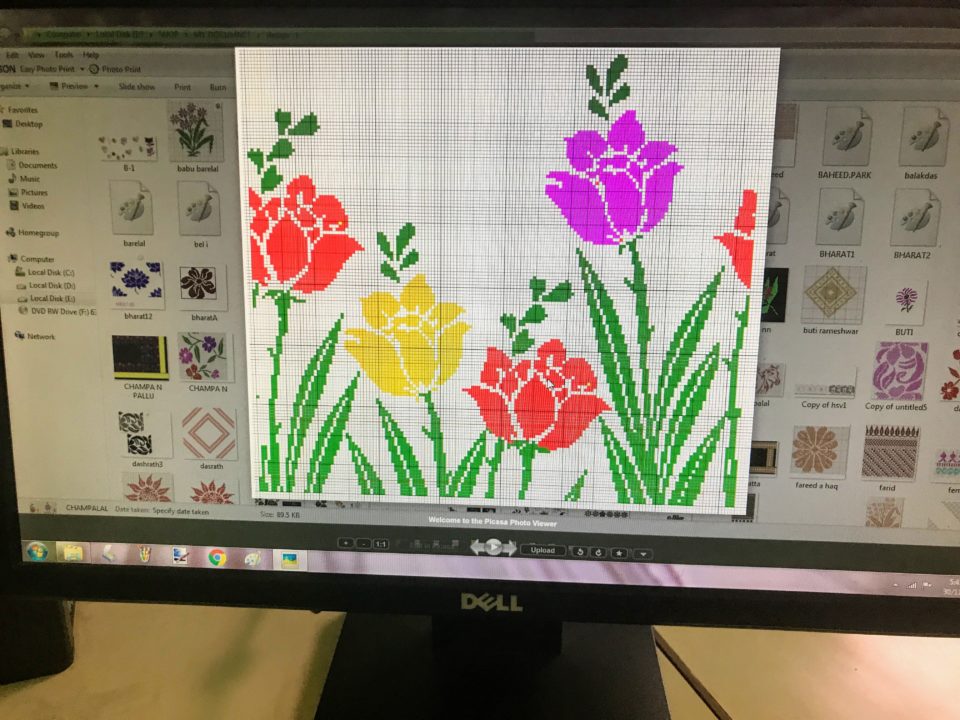

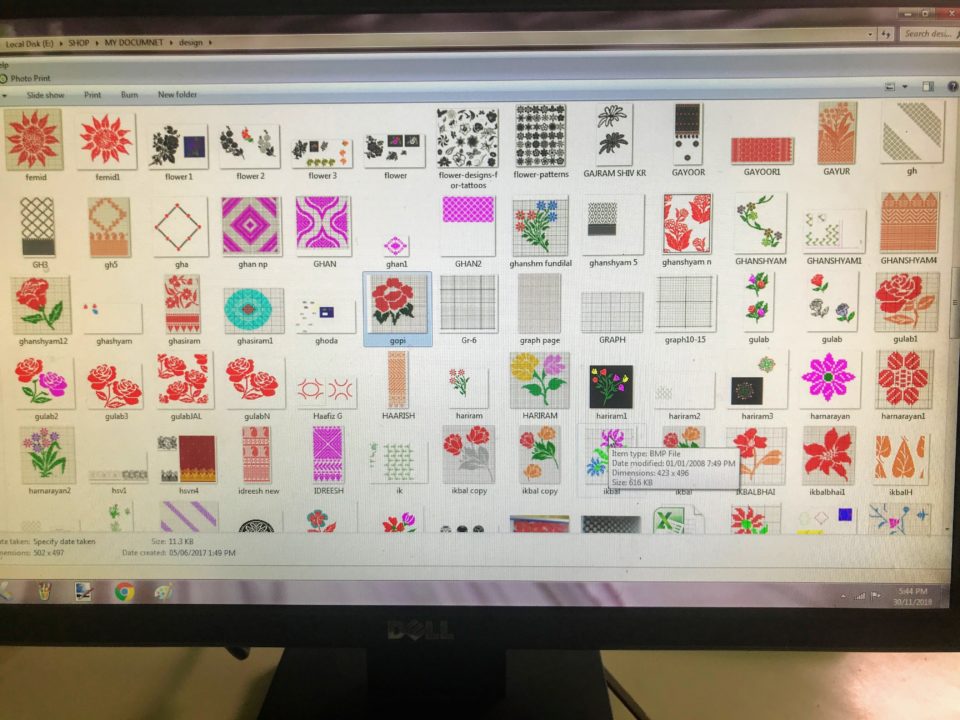

The Buttis of Chanderi

Somani-ji concurs with the book, “The Sari of India,” which says that butti-weaving came later. Some royals had a seal like the “Sooraj butti” of the Scindia royal family which would be woven into the saree.

The Wave of Muslim Migrants

The other story, corroborated by Ansari-ji is that a Muslim saint was sent to Chanderi by Nizamuddin Auliya to convert the people. He settled in Chanderi. His presence attract weavers from Bengal and Dacca, who brought with them the famed muslin techniques.

But the history of Chanderi weaving goes back centuries, says Shri. Somani.

The Myth of Aurangazeb stopping the looms

Was it true that the Mughals, particularly Aurangazeb stopped the looms, we ask.

Why would they, he responds. “The Muslim weavers were the most artistic. Much better than the (Hindu) Koli weavers.”

The original Chanderi sarees were subtle and simple, he says. Like woven air, goes the saying. It was just a plain sarees with a gold “patti” or border of a specific width.

The colours were “Laal, sunehri, morpankhi, kesari, peela, kaala, blue, the usual,” he says.

Today, Somani-ji’s grandson, Aswin, has taken over the business. He talks knowledgeably about the various techniques and their local names. Naal Pherma, for example, is a three shuttle loom. A Banewar saree has a normal jacquard warp with an extra weft for the border buttis. Daanider sarees have an extra warp of cotton insertion into the normal silk warp.

Heritage Weaves

The sarees they commission are exceptional. The Do Chashme range for example, is a reversible saree. Its price begins at Rs. 35,000 and is quite amazing to see. Subdued luxury at its best. As below.

If I could buy just one Chanderi saree, the above one is what I would start with.